If you’ve ever felt guilty about leaving the rake in the shed or putting off cutting things back, you’re not alone. Gardeners are often told that neat and tidy is the key to a healthy yard. But research keeps showing that the mess we’re tempted to clear away is often what wildlife needs most.

More than seventy percent of butterflies and moths spend the winter tucked into fallen leaves, which means every bag dragged to the curb can remove the next season’s pollinators before they ever emerge (National Wildlife Federation). Nearly a third of North America’s native bee species nest inside hollow stems, turning what looks like dead stalks into nurseries (Penn State Extension).

Even lawns tell the story—researchers found that mowing every three weeks produced two and a half times more flowers for pollinators than mowing weekly (Biological Conservation). And those logs and branches we usually haul off? Ecologists have documented more than a thousand species of insects, birds, fungi, and small mammals that rely on decaying wood at some stage in their lives (USDA Forest Service).

When you look at the numbers, a little imperfection isn’t neglect. It’s one of the simplest, most effective ways to give your garden back to the birds, bees, and butterflies that keep it alive. Here are 10 garden ‘Eyesores’ that might just make your garden the healthiest it has ever been.

1: Leaving the Leaves

Most people see fallen leaves as yard waste, but ecologists see them as habitat. Studies have shown that more than 90% of butterfly and moth species in the eastern U.S. overwinter in leaf litter—either as eggs, larvae, or pupae. When you clear away every leaf, you’re unknowingly tossing out next year’s swallowtails, luna moths, and dozens of beneficial species before they ever emerge.

Leaves also function as a natural soil amendment. A thin layer adds organic matter, feeds earthworms, and builds microbial life in a way bagged mulch never can. University of Michigan turf research even found that shredded leaves, when left on lawns, reduced weed growth the following spring by up to 80%—a surprising benefit for anyone tired of dandelions.

But not all leaves are equal. Softer ones, like maple or fruit trees, break down quickly and enrich the soil. Heavy, waxy leaves—oak, magnolia, or sycamore—tend to mat together, creating soggy layers that can smother perennials. Black walnut leaves are a special case: they contain juglone, a chemical that can stunt tomatoes, hydrangeas, and many ornamentals. Those are better composted separately or carted away.

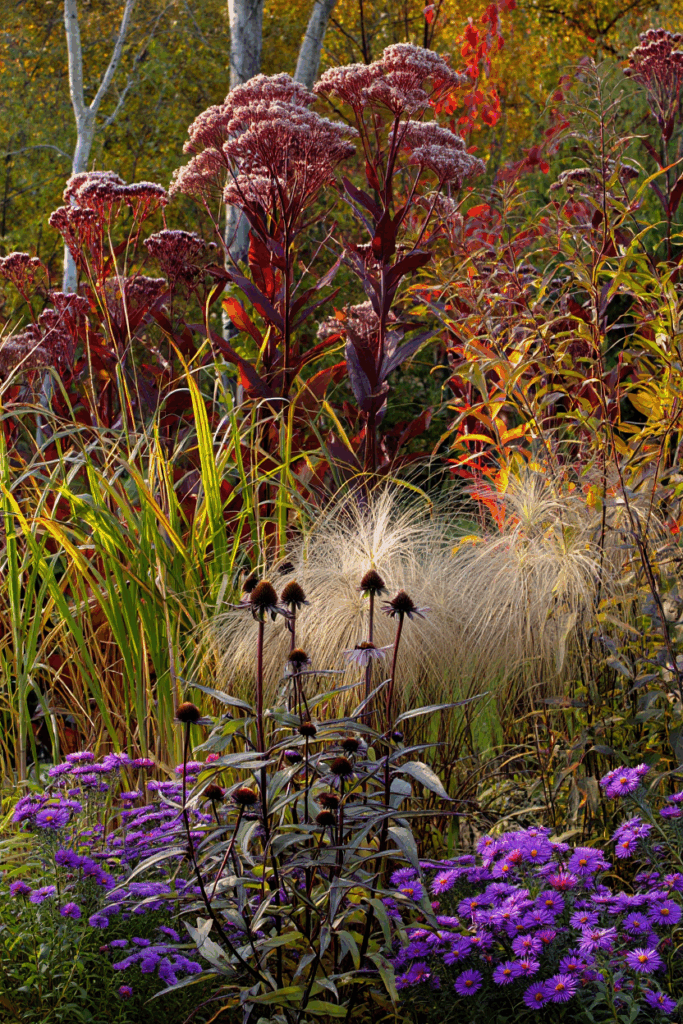

2: Don’t Be Too Quick with the Pruners

It’s tempting to clear every stem and stalk once the flowers fade, but cutting too early can strip away one of the richest habitats in your yard. Research from Penn State Extension found that nearly 30% of North America’s native bee species nest in hollow or pithy stems. By leaving stalks from plants like joe-pye weed, echinacea, and elderberry standing, you’re essentially providing high-rise housing for pollinators that won’t emerge until spring.

Seed heads are another overlooked resource. A single purple coneflower can hold hundreds of seeds, feeding finches and chickadees long after your bird feeder runs empty. Ornamental grasses do double duty, offering both cover from predators and food. In ecological terms, what looks like a “mess” is actually a year-round pantry and shelter system.

There’s also the soil science: dead foliage and stems help insulate plant crowns, keeping soil temperatures steadier during freeze-thaw cycles that often kill perennials. Gardeners who delay cutting back until early spring often see less winter dieback and stronger regrowth. The exception? Plants with powdery mildew, botrytis, or other fungal issues—those should be cleared to prevent reinfection.

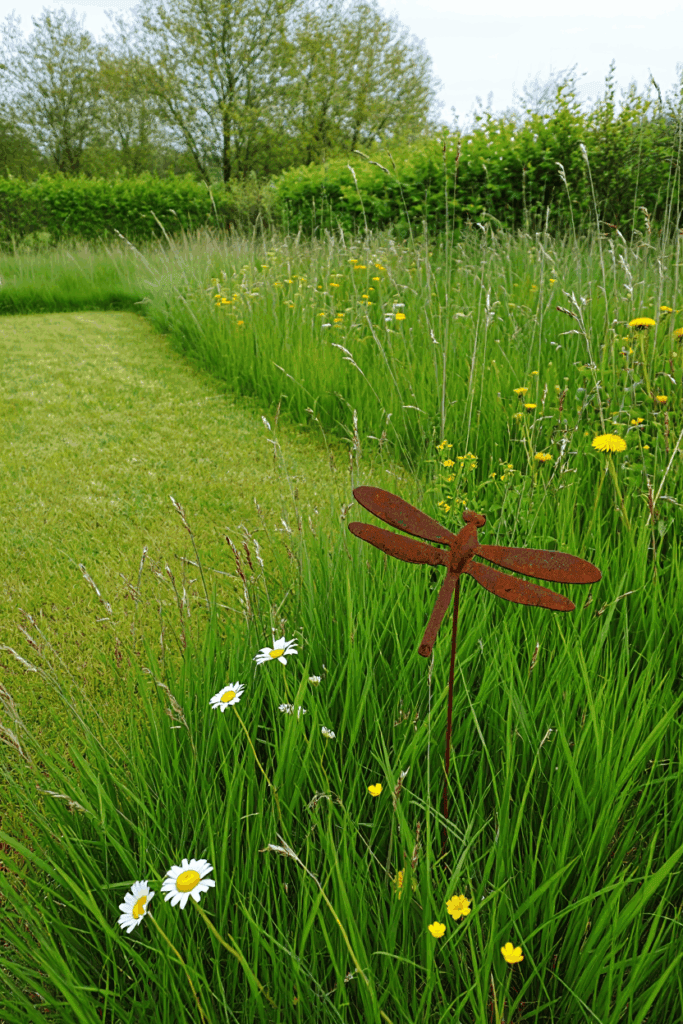

3: Letting the Lawn Go a Little Wild

A perfectly manicured lawn might look neat, but to wildlife, it’s almost a desert. Research from the University of Massachusetts found that suburban turf supports only a fraction of the insect diversity compared to mixed meadow or even patchy lawn with flowering “weeds.”

Clover, violets, and dandelions—often seen as imperfections—provide nectar and pollen at times when little else is blooming. That early-season food is what helps bumblebee queens survive long enough to start new colonies.

Longer grass blades also make a difference. Fireflies, for example, thrive in slightly taller grass where the soil stays moist and larvae can hunt slugs and snails. Mowing less frequently has been shown to increase bee abundance by as much as 60%, according to a study published in Biological Conservation.

This doesn’t mean giving up your whole lawn. Even reducing mowing to every two or three weeks, or setting aside one corner to grow a little taller, creates a mini refuge for pollinators, toads, and ground-nesting bees. By letting just part of your yard grow a bit wild, you turn sterile turf into a living patchwork that supports far more life.

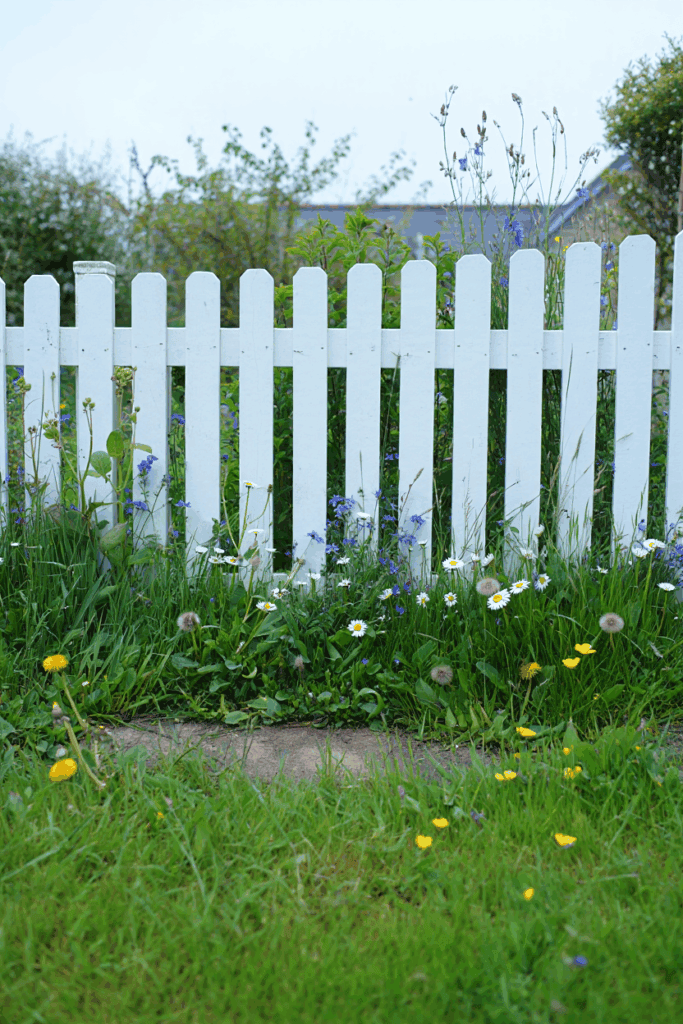

4: Keeping “Weeds” with Benefits

Most of us were taught that a “good” garden is a weed-free garden. But the truth is, many common weeds are the very plants wildlife depends on. Dandelions, for instance, often bloom weeks before ornamentals, giving pollinators a vital nectar source in early spring.

Violets are the host plant for fritillary butterflies, and goldenrod supports more than 400 species of insects—making it one of the most important late-season nectar plants in North America.

Even plants with a bad reputation can have hidden value. Plantain leaves are a food source for caterpillars, thistles produce protein-rich seeds for goldfinches, and nettles feed red admiral butterflies. The trick is knowing which “weeds” pull their weight for biodiversity and which are truly invasive.

You don’t have to let them take over. A balanced approach—allowing clumps of violets in shady corners, leaving a patch of goldenrod at the back of the border, or tolerating a few dandelions in spring—creates stepping stones of habitat without sacrificing design.

5: Leaving Logs to Decay

When a tree limb falls or a log begins to rot, the natural instinct is to clean it up. But in healthy ecosystems, dead wood is essential. More than a thousand species of insects, birds, amphibians, and mammals in North America rely on decaying wood at some point in their life cycle. Beetle larvae bore through the softening fibers, woodpeckers follow to feed on them, and salamanders slip into the damp crevices for shelter.

As the log continues to break down, fungi and microbes recycle its nutrients back into the soil, enriching it more steadily than any bagged fertilizer could. The porous wood also acts like a sponge, holding onto rainwater and keeping the surrounding soil moist long after storms have passed. That stable moisture creates microhabitats where mosses, ferns, and shade perennials thrive.

So instead of hauling every branch away, leave some to decompose naturally on the ground. A log returning to soil is part of the life cycle your garden depends on—feeding the earth, sheltering wildlife, and building fertility for the next generation of growth.

6: Letting Flowers Go to Seed

Deadheading is one of those chores many gardeners do on autopilot, but leaving some flowers to go to seed changes the way your garden supports life. Coneflowers, black-eyed Susans, and sunflowers can each produce hundreds of seeds that feed goldfinches, chickadees, and sparrows through the leanest months of winter.

Ornamental grasses are just as valuable—seed heads offer both food and cover, especially when snow and ice make natural resources scarce.

For insects, seed heads and hollow stems double as shelter. Lacewing larvae, native bees, and overwintering caterpillars often hide inside the dried structures, using them as safe havens until spring. Researchers at the Xerces Society note that many solitary bees don’t emerge from their stem nests until April or May, which means cutting everything back too soon can wipe out a season’s worth of pollinators.

There’s a soil benefit, too: dried stalks catch windblown leaves and snow, which adds insulation and moisture to the ground around your perennials. Come spring, you can clip them down just before new growth pushes through, returning that organic matter to the soil.

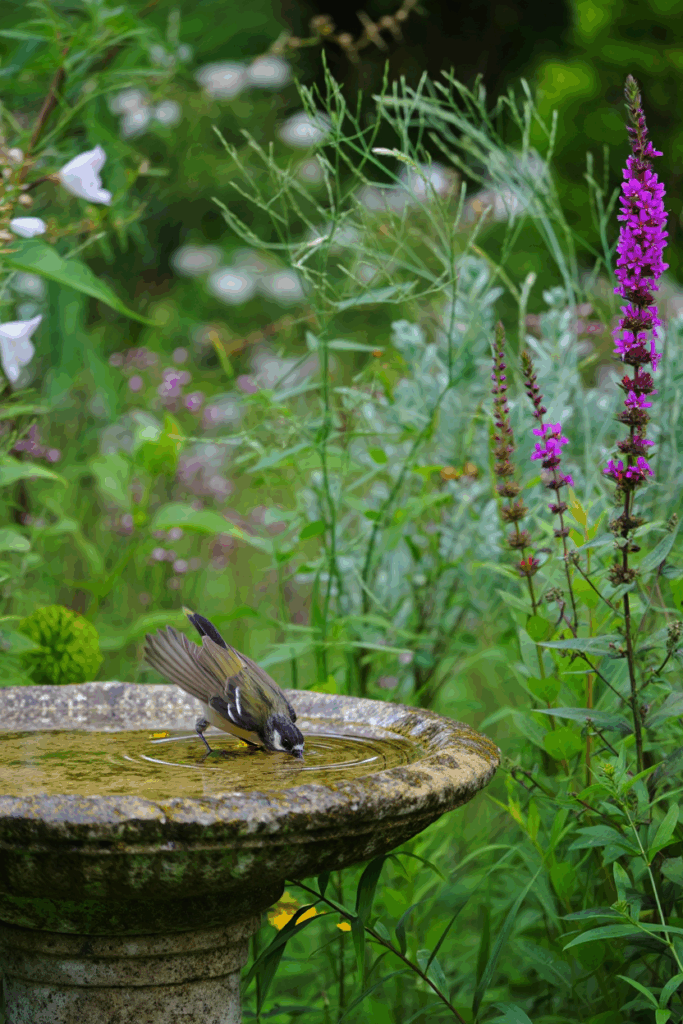

7: Keeping Water Sources Imperfect

A crystal-clear birdbath might look pretty to us, but nature doesn’t need sterile perfection. Small amounts of organic matter—like a little mud, algae, or fallen leaves—actually make water sources more useful for wildlife.

Butterflies and bees practice what’s called “puddling,” sipping from damp, mineral-rich mud to get salts and nutrients they can’t find in nectar. Hummingbirds do the same, balancing their sugar-heavy diets with trace minerals from muddy water.

Even birds building nests depend on a bit of mess. Barn swallows, phoebes, and robins use wet soil to form and reinforce their nests. Without easy access to mud, many of these species struggle to raise young successfully. A “too clean” water feature deprives them of that building material.

The key isn’t to let your water sources stagnate, which can attract mosquitoes, but to allow them to stay natural. A shallow dish with pebbles and a little silt, a low area in the yard where rain collects, or even a birdbath refreshed every few days is enough. Instead of scrubbing everything spotless, think of water as a living resource—messy, mineral-rich, and essential for far more creatures than just thirsty birds.

8: Allowing a Little Mud

Most gardeners see mud as a nuisance they try to drain away, cover up, or keep from being tracked into the house. For wildlife, though, a muddy patch can be a lifeline. Many butterflies, including swallowtails and monarchs, gather at damp soil to sip water mixed with salts and minerals that nectar cannot provide. Researchers have found these nutrients are critical for reproduction, since males transfer them to females during mating, which improves the survival of their young.

Mud also works as construction material. Robins, barn swallows, and phoebes use it to shape and strengthen their nests. If they cannot find enough wet soil, nesting often fails. Mason bees depend on it as well, sealing their tubes with carefully packed layers of mud to protect developing larvae.

You don’t need to flood the yard. A low corner that stays damp after rain or a shallow dish of moist soil is enough. What may look messy to us is exactly what keeps pollinators and birds thriving.

9: Piling Brush in a Corner

That stack of twigs and branches you meant to haul away can become one of the most valuable wildlife shelters in your yard. A brush pile offers protection for wrens, cardinals, and sparrows during storms and bitter cold. Small mammals like rabbits and chipmunks use the cover to escape predators, and overwintering insects find safe hiding places in the nooks.

As the pile settles and decays, it creates layers of habitat. The upper branches provide perches for birds, while the damp, shaded base becomes a refuge for toads, salamanders, and ground beetles. Over time, fungi and microbes move in, breaking down the wood and adding nutrients back to the soil beneath.

A brush pile does not need to be huge to make a difference. Even a modest stack in the back corner of your yard can provide year-round habitat. What looks untidy is really a small, living refuge that keeps your garden buzzing, hopping, and singing.