You’ve seen it before — and it probably made your stomach drop.

A plant you’ve cared for suddenly looks wrong. Shoots erupt where a single branch should be. Stems flatten and twist as if they’ve been softened, pressed, reshaped. Flowers open with too many petals, too many centers, no longer resembling the blooms you were waiting for. Your first thought is almost always the same: What happened?

For gardeners, that moment cuts deeper than most people realize. These aren’t just plants — they’re weeks of attention, routines built around watering and watching, quiet optimism invested in every new leaf. When something deforms instead of growing, it feels like catching a problem too late… or worse, not understanding it at all.

What’s unsettling is that these changes aren’t random. They’re deliberate responses. When a plant can’t escape stress, disease, parasites, or hormonal disruption, it alters itself instead. Growth speeds up in the wrong places. Tissues swell, twist, or collapse. The plant doesn’t scream — it reshapes itself, quietly signaling that something has gone deeply off course.

This list isn’t about garden scares or rare monstrosities. It’s about recognizing the warning signs plants show when they’re under pressure. Because once you learn to read these distorted forms, they stop feeling mysterious — and start feeling like messages you can’t afford to ignore.

1. Witch’s Broom (Hormone Hijacking & Meristem Overactivation)

You usually notice it mid-stride — passing a plant you’ve walked by for years — when one branch suddenly looks wrong. Not damaged. Not dying. Just unnaturally busy. A dense explosion of thin shoots bursts from a single point, far more growth than the plant was ever meant to produce there.

This growth appears widely across Zones 4–9, especially through northern and central regions, the eastern half of the country, and parts of the Pacific Northwest and upper South. It’s most often seen on everyday landscape plants — maples, cherries, junipers, spruces, and roses — the kinds of plants that quietly shape streets, yards, and park edges.

Witch’s broom is not a single disease, but a growth response caused by specific biological disruptions. The most common triggers include:

- Phytoplasma infections that interfere with normal hormone signaling

- Eriophyid mites that stimulate excessive bud activation

- Certain fungal infections that alter growth regulators at the shoot tip

In each case, the same thing happens: dormant buds are forced to grow simultaneously, overwhelming the plant’s ability to control spacing and direction.

What makes witch’s broom unsettling is that the plant doesn’t slow down — it accelerates in the wrong place. Growth continues aggressively, but without structure or balance, turning what should have been measured branching into a crowded mass that quietly pulls energy away from the rest of the plant.

2. Fasciation (Meristem Fusion & Growth-Point Collapse)

It doesn’t read as damage at first. A stem widens and flattens into a ribbon, sometimes twisting as it grows, sometimes carrying flowers that look stretched, doubled, or fused along one edge. The form feels intentional — sculpted rather than injured.

Fasciation appears across Zones 3–10, showing up in midwestern gardens, southern vegetable beds, western backyards, and cooler northern climates alike. Sunflowers, tomatoes, coneflowers, zinnias, asparagus, broccoli, and squash are frequent examples — plants expected to grow upright and orderly, yet prone to dramatic distortion when early signals fail.

What’s happening isn’t random mutation, but a breakdown at the growing tip, known as the meristem. Fasciation occurs when:

- Physical injury damages the meristem before growth stabilizes

- Sudden temperature swings disrupt cell division timing

- Bacterial interference alters growth regulation

- Hormonal overload forces multiple growth points to act as one

Instead of producing a single, round stem, the plant merges growth zones into a flattened, expanded structure. Growth continues — vigorously — but without spacing, symmetry, or restraint.

What lingers isn’t weakness, but evidence. Once fasciation forms, the plant can’t undo it. The distorted stem becomes a permanent record of a moment when growth instructions collided and never separated again.

3. Rosette-Type Stunting (Phytoplasma & Growth-Regulator Injury)

At first glance, it looks deliberate. The plant stays low and compact, leaves arranged tightly at the base in a clean, circular rosette. Days turn into weeks, and nothing changes. No stem rises. No flowers appear. The plant remains locked in place.

This growth pattern appears across Zones 4–9, especially after cool, uneven springs, sharp temperature swings, or in areas with regular lawn and landscape chemical use. Lettuce, carrots, strawberries, sunflowers, asters, and other broadleaf plants are frequent examples — species that rely on internode elongation to transition into flowering.

What’s happening is not a single disease, but a failure of stem elongation caused by specific disruptions, most commonly:

- Phytoplasma infections (the same class of organism behind aster yellows)

- Growth-regulator herbicide exposure (2,4-D, dicamba drift)

- Severe nutrient imbalance, especially phosphorus or micronutrients

- Early viral interference during active growth

In each case, leaf production continues while the signal to extend upward is suppressed. The plant keeps growing — just sideways instead of forward.

The result isn’t collapse, but arrest. Growth accumulates without progression, leaving the plant suspended in an early developmental state it can’t exit on its own.

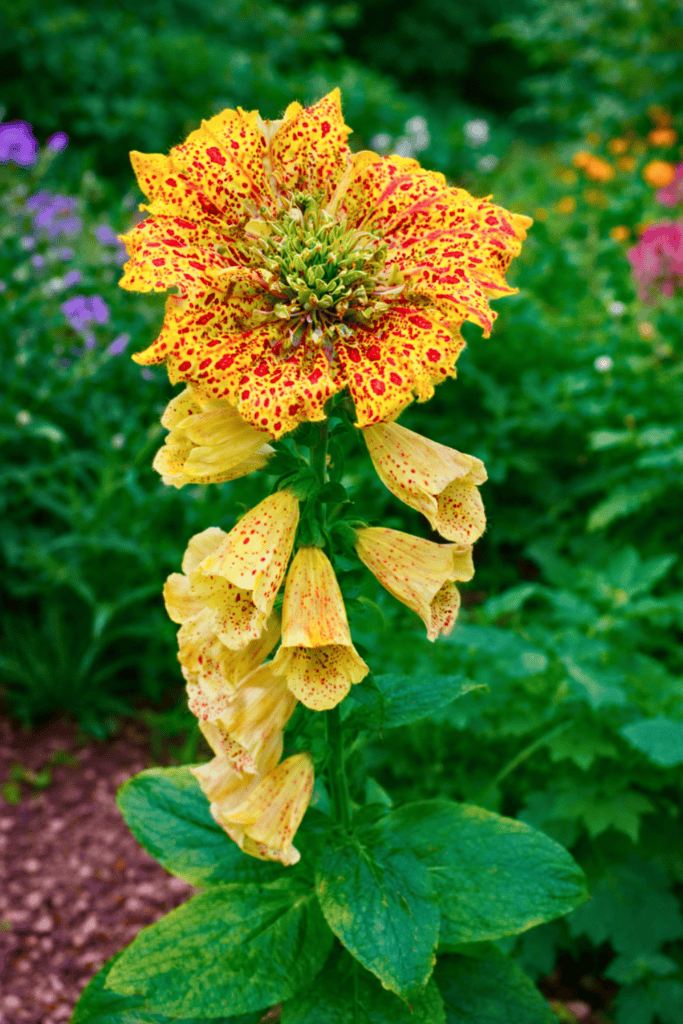

4. Monster Flowers (Fasciation, Peloria & Floral Mutations)

Some blooms arrive already breaking the rules. Petals multiply, centers fuse, symmetry collapses, and the flower grows larger or stranger than anything around it. It doesn’t look damaged — it looks rewritten.

These abnormal blooms appear across Zones 5–10, often after temperature shocks during bud formation, prolonged heat, or other developmental stress. Roses, sunflowers, coneflowers, hibiscus, camellias, zinnias, tulips, and daffodils are frequent examples — plants expected to bloom predictably, yet capable of dramatic failure when early signals misfire.

What we call “monster flowers” are not caused by a single disease. They are the visible result of specific floral development errors, most commonly:

- Fasciation — where multiple flower centers fuse into one flattened or oversized bloom

- Peloria — where flowers lose their normal symmetry and repeat petal structures

- Phyllody — where floral parts partially turn leaf-like due to phytoplasma

- Virus-induced floral deformities — where normal organ separation breaks down

These disruptions happen early, while the flower is still forming inside the bud. Once that blueprint slips, the flower simply follows the wrong instructions all the way to bloom.

What makes these flowers unsettling is their isolation. The plant around them often looks perfectly healthy — green leaves, upright stems, normal growth — while the bloom alone preserves the moment when development went off course.

5. Gall Growths (Insect-Induced & Bacterial Tissue Hijacking)

They seem to appear overnight — swollen bumps, knots, or blistered forms pushing out from leaves, stems, or twigs. Some are smooth and marble-like. Others are spiky, ridged, or corky. Once you notice one, you start spotting them everywhere.

Gall growths occur across Zones 3–10, especially in wooded areas, older neighborhoods, and long-established landscapes. Oaks, maples, willows, roses, grapes, and hickories are frequent hosts. What forms the gall isn’t decay — it’s direct manipulation of plant growth at a microscopic stage.

These structures are created when:

- Gall-forming insects (such as wasps, midges, aphids, or mites) inject chemical signals during egg-laying

- Bacteria (most notably Agrobacterium in crown gall) alter normal cell division

In response, the plant builds a custom growth — a structure designed by its own tissue, but optimized to protect and feed something else.

What makes galls unsettling isn’t their size, but their intent. The plant isn’t reacting after damage occurs. Its development is redirected from the very beginning, shaping living tissue into a controlled environment that looks pathological but is highly organized.

Long after the insect has emerged or the infection has passed, the gall remains — a permanent record of an interaction that happened early, quietly, and entirely out of sight.

6. Proliferation (Floral Reversion & Meristem Misfiring)

It catches your eye because the flower doesn’t know when to end. A bloom finishes opening — and instead of fading, something new pushes out from its center. Another stem. Another flower. Sometimes an entire cluster where seeds should have formed.

This phenomenon appears across Zones 4–10, especially in regions with long flowering seasons, mild winters, or unstable spring temperatures. Coneflowers, black-eyed Susans, daisies, roses, phlox, and carnations are frequent examples — plants whose flowering cycles are normally well defined.

Proliferation isn’t random overgrowth. It happens when floral meristems lose their identity and revert back to vegetative growth, a process known as floral reversion. This breakdown is most often triggered by:

- Hormonal disruption during flowering

- Sudden heat or cold shifts that interrupt developmental timing

- Viral or phytoplasma interference

- Extended environmental stress that prevents the flower from completing its cycle

Instead of transitioning cleanly from flowering to seed formation, the plant slips backward. Growth resumes where reproduction should have ended.

What makes proliferation unsettling is its limbo. The flower never resolves into seed, and growth never fully resets. The plant remains caught between stages, quietly exposing how fragile the boundary is between flowering and growth when developmental signals blur.

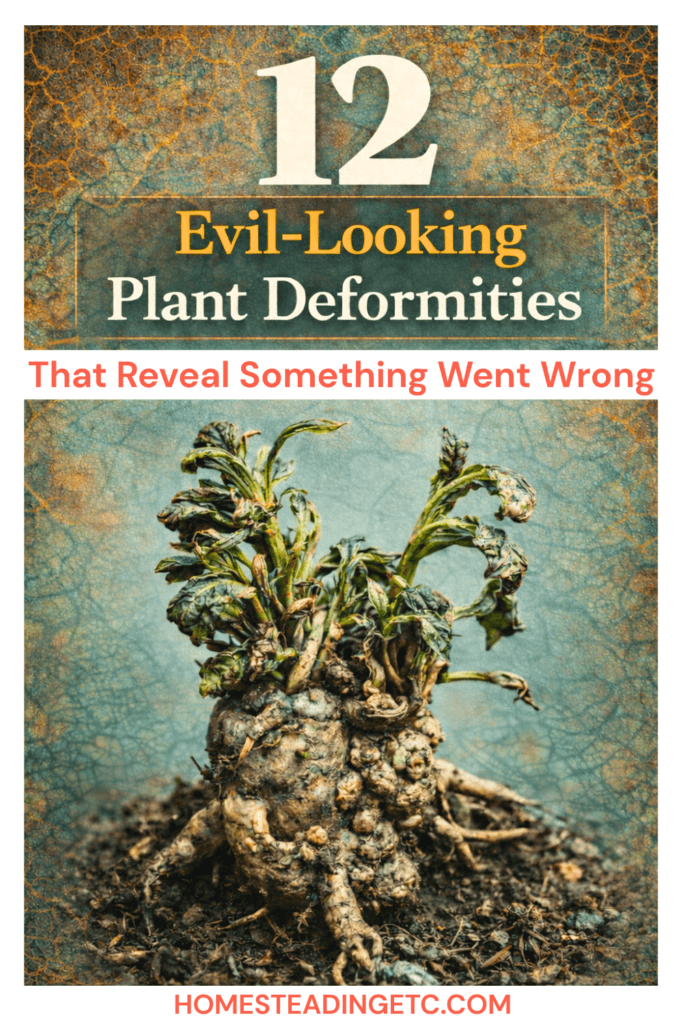

7. Clubroot Disease (Swollen, Deformed Root Masses)

You never see it from above. The leaves may wilt, yellow, or lag behind — but the real horror is underground. When the plant is pulled, the roots are no longer roots at all. They’re swollen into thick, knotted masses, distorted and bulbous, like something grown wrong on purpose.

Clubroot appears across Zones 4–9, especially in cool, moist soils and long-used garden beds. Brassicas are its primary victims — cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, radishes, and mustards. The cause is not a fungus, but a soil-borne pathogen that invades root tissue and forces cells to divide uncontrollably.

The result isn’t decay. It’s expansion. Normal fine roots disappear, replaced by grotesque clubs that can no longer absorb water or nutrients efficiently. Above ground, the plant starves slowly. Below ground, the damage is already complete.

What makes clubroot especially disturbing is its concealment. The plant struggles quietly until it can no longer sustain itself — and only then does the buried deformity reveal how thoroughly growth was hijacked from the inside out.

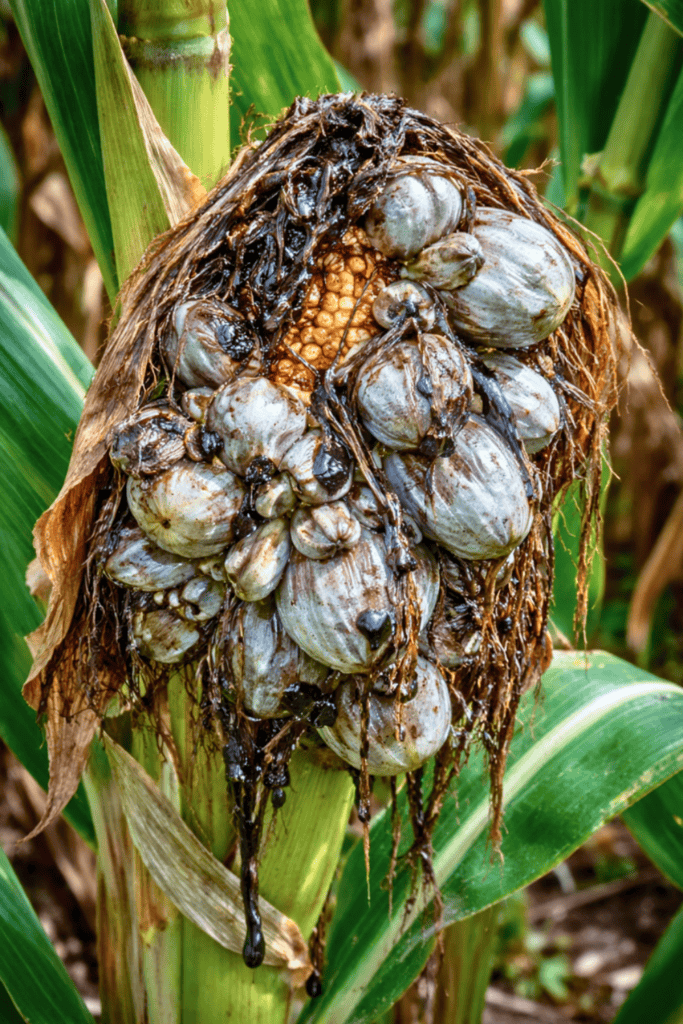

8. Smut Diseases (Tumor-Like Spore Sacs & Explosive Infection)

At first, it looks like swelling. Then the tissue darkens, stretches, and inflates into blistered sacs that barely resemble plant parts anymore. When they rupture, they release clouds of black or gray spores — turning healthy tissue into something that looks burned, rotten, or possessed.

Smut diseases appear across Zones 3–10, most famously in corn, grasses, and cereal crops, but also on ornamentals. The pathogens infect young tissue early, redirecting normal development into massive spore-filled tumors. Corn smut is the most infamous example — ears, tassels, and stems swelling into grotesque, balloon-like growths before bursting open.

What makes smut uniquely unsettling is visibility. This isn’t subtle distortion or slow decline. The plant is visibly transformed — organs replaced by sacs designed for one purpose only: reproduction of the pathogen.

When the sacs rupture, the plant’s original structure is gone. All that remains is powder — evidence that growth was never the goal, only conversion.

9. Fused Fruits (Carpel Fusion & Early Floral Damage)

You rarely notice it until harvest. Two fruits share the same skin, the same curve, sometimes even the same stem — as if they were pressed together before they ever had the chance to become separate.

This occurs across Zones 4–9, most often in regions where spring temperatures fluctuate sharply between warm days and cold nights. Tomatoes, strawberries, apples, peaches, peppers, and squash are common examples. The cause doesn’t lie in the fruit itself, but much earlier — at the flower stage.

Fused fruits form when adjacent floral carpels merge during early development, a process known as carpel fusion. This usually happens after:

- Cold injury or heat stress damages flower buds

- Hormonal disruption interferes with normal ovary separation

- Abnormal pollination timing overlaps neighboring floral tissues

Once the ovaries fuse, the fruit simply follows that altered blueprint to maturity.

What makes fused fruits deceptive is how late the evidence appears. The plant grows normally, flowers on schedule, and sets fruit without warning. Only at harvest does the plant reveal a record of stress that occurred weeks earlier, hidden deep inside the developing flower.

Fused fruits stand as delayed proof that early developmental mistakes don’t disappear — they wait, fully formed, until the end of the season to surface.

10. Tumorous Crown Galls (Agrobacterium-Induced Cellular Reprogramming)

You usually find them low on the plant, right where stem meets soil — hard, knotted swellings that don’t soften, crack, or fade with time. They sit quietly at the base, expanding slowly, season after season.

Crown galls appear across Zones 4–9, most often in long-established beds, orchards, vineyards, and perennial plantings. Roses, fruit trees, grapes, and other woody plants are frequent hosts. The cause is bacterial — most commonly Agrobacterium — which enters through wounds created by planting, pruning, insects, or soil movement.

Once inside, the bacterium does something unusual. It transfers genetic instructions into the plant’s own cells, forcing them to divide uncontrollably. The gall isn’t foreign tissue — it’s the plant’s growth system rewritten from within.

What sets crown galls apart from surface deformities is their location. They form precisely where water and nutrients must move upward, quietly restricting flow long before the plant shows obvious decline above ground.

The gall becomes more than a symptom. It’s a structural takeover — evidence that some damage doesn’t announce itself loudly, but settles in early and reshapes the plant from its foundation upward.

11. Southern Blight (White Fungal Webs & Collapsing Plants)

It starts at soil level. A white, cottony mass creeps outward, wrapping the base of the stem like moldy spider silk. Within days, the plant collapses completely — stems rotted through, leaves still green but cut off from support.

Southern blight appears across Zones 7–11, especially during hot, humid weather. Tomatoes, peppers, beans, squash, hostas, and countless ornamentals are common victims. The pathogen attacks the stem at the soil line, producing thick fungal mats and small, round survival bodies that resemble mustard seeds scattered across the surface.

What makes southern blight grotesque is speed and texture. Plants don’t slowly decline — they fall over as if severed. The white fungal growth is highly visible, spreading across mulch and soil like living fabric.

The plant doesn’t look diseased at first. It looks strangled at the base, leaving a scene that feels closer to decay than illness.

12. Black Knot Disease (Charcoal-Black Tumors on Branches)

You don’t notice it until winter. Leaves are gone, branches are bare — and suddenly thick, jet-black growths stand out against the wood. Hard, swollen, cracked masses cling to twigs and limbs like burned tumors that never healed.

Black knot appears across Zones 3–8, especially in regions with cool, wet springs. It primarily attacks cherries and plums, both ornamental and fruiting. The disease starts quietly in young green tissue, then slowly expands over months, turning into elongated, coal-black knots that can wrap completely around a branch.

What makes black knot visually disturbing is contrast and texture. The growths are rough, irregular, and unnaturally dark — looking more like something grafted onto the tree than grown by it. As they age, they crack and split, exposing even more warped tissue beneath.

The branch doesn’t rot away immediately. It stays alive, feeding a mass that looks dead, burned, and foreign — until the knot eventually strangles the limb from the inside.