Let’s be honest: February isn’t exactly the most glamorous month in the garden. Everything looks a bit “crunchy,” the ground is usually a muddy mess, and it’s tempting to just stay inside and wait for the tulips to do the heavy lifting. But here’s the secret that the pros won’t tell you: the work you do in the next few weeks determines whether your summer garden looks like a lush paradise or a floppy, leggy disaster.

Right now, your plants are in a deep sleep, but the alarm clock is about to go off. If you wait until March or April to start pruning, you’re too late. Once the sap starts flowing and the plant puts energy into those old, tired branches, cutting them back becomes a shock to the system. But if you strike now, you’re essentially “hacking” the plant’s biology—forcing it to divert all that stored winter energy into brand-new, muscular stems that can actually support a heavy load of flowers.

We aren’t just tidying up; we’re setting the stage for a growth spurt that will make your neighbors wonder what kind of magic fertilizer you’re using. It’s about trading last year’s woody, brittle skeletons for fresh, vibrant growth that stays upright and blooms its heart out.

1. Butterfly Bush (Buddleja davidii)

Common in USDA Zones 5–9, the Buddleja is a rapid-growth species that thrives on a “hard reset.” Biologically, this plant is a “new wood” bloomer, meaning its flower primordia only develop on fresh green tissue. If you leave the old, woody skeleton, the plant’s auxin (a growth hormone) stays concentrated at the tips, resulting in tall, spindly branches that easily “lodge” or collapse under their own weight.

By cutting the shrub back to 12–24 inches before the March sap rise, you force the plant to divert its stored root energy into adventitious buds at the base. This creates a thicker vascular system—larger xylem and phloem—which can move water more efficiently. The result is a sturdier, compact bush with significantly larger flower panicles that won’t flop over during a summer downpour.

2. Smooth Hydrangea (Hydrangea arborescens)

Commonly found in USDA Zones 3–9, the ‘Annabelle’ type hydrangea is a classic “new wood” bloomer. Unlike the blue Mopheads that set buds in the fall, these species develop their flower primordia entirely in the spring. If you leave the old, spindly canes, the plant suffers from nutrient competition, forcing energy through narrow, weak stems that eventually collapse under the weight of the massive flower heads.

Pruning these back to about 12 inches (or just above the second or third node from the ground) before March stimulates the growth of thicker, more lignified stems. This structural reinforcement ensures the plant has the internal “piping” to support those heavy blooms during mid-summer humidity and rain.

3. Russian Sage (Salvia yangii)

A staple in the arid West and Midwest (Zones 5–9), Russian Sage is a sub-shrub that develops a semi-woody base. If left unpruned, the plant experiences desiccation—the winter wind dries out the previous year’s growth, leaving a brittle, “ghostly” structure. If new growth emerges from these high, dried-out points, the plant becomes top-heavy and “splits” in the center, a phenomenon known as lodging.

By pruning the stems back to roughly 6 inches above the soil line in late February, you encourage growth from the “crown,” the area with the highest concentration of meristematic tissue. This ensures the new stems are dense and rich in cellulose, providing the structural integrity needed to remain upright without staking during the heat of July.

4. Rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus)

Popular across USDA Zones 5–9, this hardy hibiscus is often left to grow into a tall, spindly tree, but it actually blooms best on current-season growth. Without a late-winter prune, the plant’s apical dominance directs energy to the very tips of long, thin branches, resulting in a “weeping” effect where flowers are sparse and hard to see.

Pruning these back by about one-third of their height before the March bud-break encourages “branching out” from lower lateral buds. This creates a fuller, more rounded canopy with a higher density of flower-producing nodes. Additionally, thinning out the center improves air circulation, which is vital in the humid Eastern US to prevent fungal pathogens like powdery mildew from taking hold.

5. Ornamental Grasses (Schizachyrium scoparium & Panicum virgatum)

Native US grasses like Little Bluestem and Switchgrass are prized for their winter structure, but they require a hard shearing before the spring “green-up.” Biologically, these are warm-season grasses that remain dormant until soil temperatures rise. If you don’t cut the dead foliage back to about 3–4 inches from the crown by late February, you create a physical barrier that traps moisture and shades out the new emerging blades.

Removing this old biomass prevents “center-out” rot and ensures that the sun can hit the rhizomes directly, warming the soil and triggering a faster metabolic start. This early-season sunlight exposure leads to a much tighter, more upright habit, preventing the grasses from “flopping” or splaying open when they hit their full height in late summer.

6. Hybrid Tea and Floribunda Roses (Rosa)

Whether you are in the rain-soaked Pacific Northwest or the humid Southeast, roses (Zones 5–9) are susceptible to apical inhibition, where the topmost bud prevents lower buds from developing. If you leave the long, spindly “canes” from last year, the plant wastes its initial spring energy on weak, distant growth that produces small, inferior flowers on stems that can’t support their weight.

By pruning the canes back to an outward-facing bud—about 12 to 18 inches from the ground—you redirect the plant’s hormones to create a vase-like shape. This open center is scientifically critical for transpiration and airflow, which drastically reduces the “leaf wetness duration” that allows fungal spores like Black Spot (Diplocarpon rosae) to germinate. This results in a structurally sound plant with thick, nutrient-rich canes.

7. Late-Flowering Clematis (Group 3)

In the US, Group 3 varieties like ‘Jackmanii’ or ‘Sweet Autumn’ (Zones 4–9) are biologically programmed to flower on the current season’s green growth. If the old vines are left intact, the plant’s sap pressure is spread too thin across a massive network of dead or dormant wood. This leads to “bare legs”—a common sight in American gardens where the bottom six feet of the trellis are an unsightly brown tangle, while flowers only appear at the very top.

Cutting the entire plant down to about 12 inches from the ground, just above a pair of healthy, swelling buds, triggers a vigorous “rebound” effect. By concentrating the root system’s stored carbohydrates into just a few nodes, the plant produces thick, rapid-climbing vines. This ensures a lush, leafy display from the ground up and a much higher density of flower buds per square foot of trellis.

8. Red-Twig Dogwood (Cornus sericea)

Commonly used in Zone 3–8 landscapes for its winter color, the Red-Twig Dogwood relies on a process called compensatory growth. The vibrant red pigment (anthocyanin) is most concentrated in the “juvenile” bark of stems less than two years old. As the wood matures, it develops a corky layer that turns a dull grayish-brown. If you don’t intervene, the plant becomes a lackluster shrub with very little winter appeal.

By employing the “rule of thirds”—removing one-third of the oldest, thickest canes right at the base—you stimulate the plant to produce new “whips.” This selective thinning prevents the shrub from becoming overgrown while maintaining a constant cycle of young, brightly colored wood. This technique ensures the plant remains a high-impact architectural feature in the snowy winter months across the northern US.

9. Bluebeard (Caryopteris x clandonensis)

Thriving in the drier regions of the US (Zones 5–9), Bluebeard is a deciduous sub-shrub that frequently suffers from winter die-back. Because it produces its blue, nectar-rich flowers on the tips of “new wood,” any old stems left from last season act as a metabolic drag. If you don’t cut it back, the plant develops a “hollow” woody center that is structurally weak and prone to splitting under the weight of summer pollinators.

Hard pruning the stems back to about 6 inches—just above the lowest viable buds—concentrates the plant’s energy into a dense, mounded habit. This maximizes the number of flowering terminals per square inch and ensures the stems are rigid enough to stay upright. In the heat of late August, this structural integrity is what allows the plant to provide a consistent, vibrant blue carpet of color.

10. Beautyberry (Callicarpa americana)

A native powerhouse in the Southeast and hardy up to Zone 6, the Beautyberry is prized for its iridescent purple fruit clusters. Biologically, these berries only develop at the axillary nodes of current-season growth. If the plant is left unpruned, it follows a “weeping” growth habit where the branches become increasingly thin and elongated, leading to poor fruit density and a “scraggly” appearance in the landscape.

By cutting the shrub back to a height of 12 inches in late February, you trigger a vigorous hormonal response from the root crown. This results in sturdy, upright canes that can support a significantly higher “berry load” without snapping. This hard prune essentially resets the plant’s reproductive cycle, ensuring that by autumn, every branch is packed with the vibrant berries that are a critical late-season food source for American songbirds.

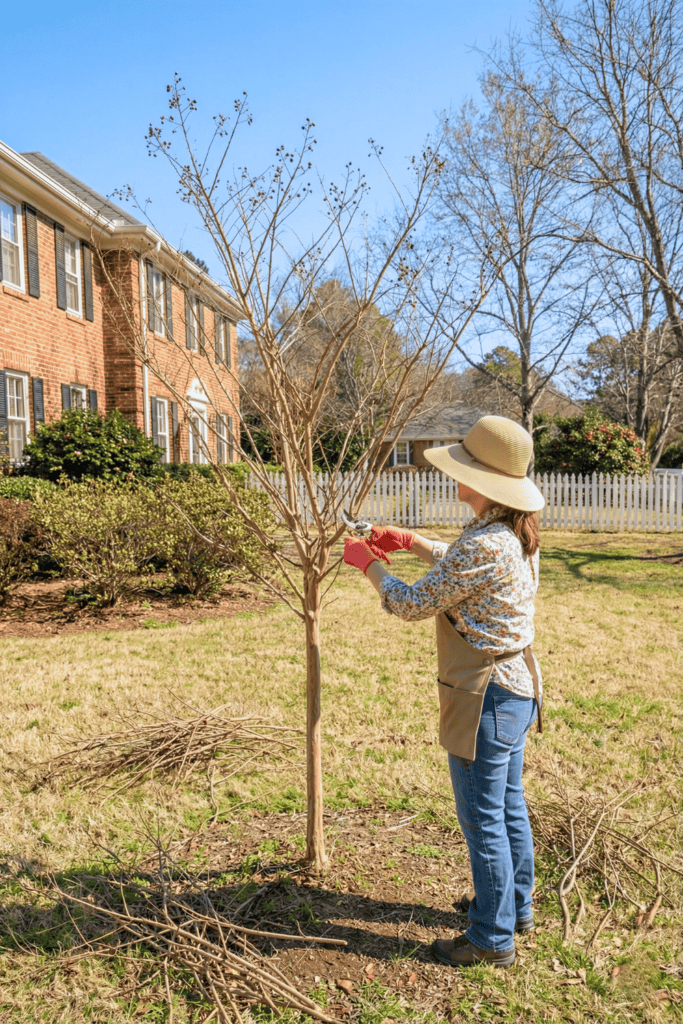

11. Crepe Myrtle (Lagerstroemia)

Ubiquitous across the Southern US and extending into Zone 6, the Crepe Myrtle is often a victim of “Crepe Murder”—the practice of topping them into ugly stumps. Scientifically, this is counterproductive as it creates weak, “knobby” scar tissue that is prone to disease. However, a strategic late-winter thinning is essential. Because these trees bloom on new wood, removing the thin, “spaghetti” growth and any crossing branches ensures the plant doesn’t waste energy on stems too weak to support the heavy flower panicles.

By focusing on “structural pruning”—removing the smaller, interior shoots and thinning the canopy—you improve sunlight penetration to the lower meristems. This results in stronger, thicker branches that can hold the weight of summer blooms even during the heavy rains common in the American South. This approach maintains the tree’s natural bark beauty while maximizing its floral display.

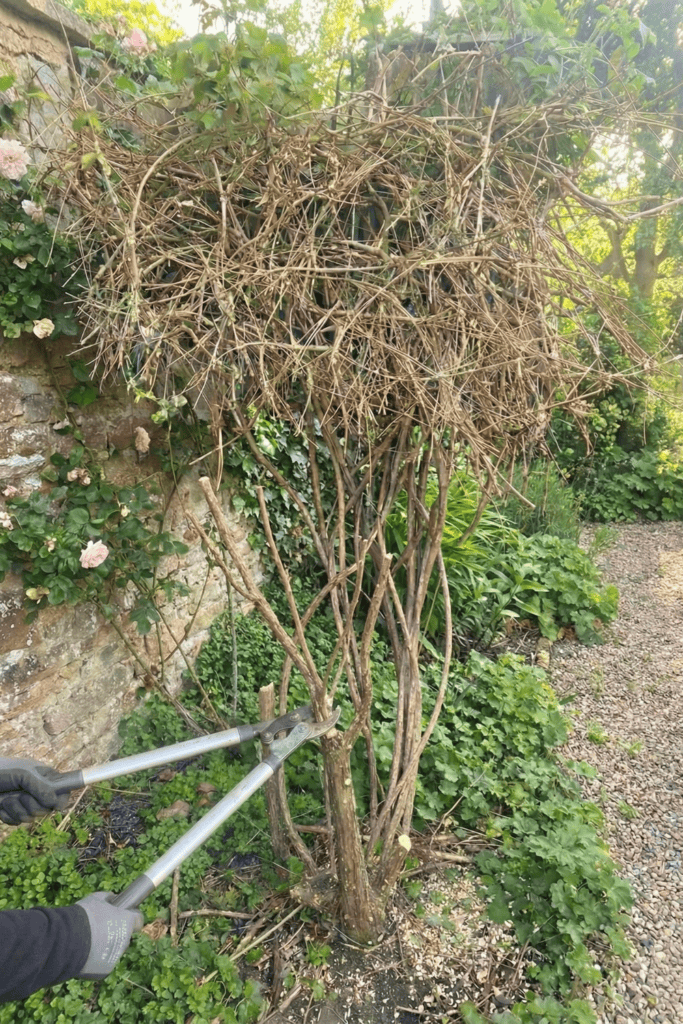

12. Summer-Flowering Spirea (Spiraea japonica)

Commonly used as a foundation plant across USDA Zones 3–8, varieties like ‘Gold Mound’ or ‘Little Princess’ tend to accumulate “twiggy” dead wood in the center of the mound. Biologically, Spirea is a prolific brancher; without annual intervention, the interior of the shrub becomes shaded out, leading to senescence (premature aging) of the inner stems. This results in a “doughnut” effect where the plant is green on the outside but completely bare and brown on the inside.

By shearing the top one-third to one-half of the plant into a neat, rounded mound before March, you remove the terminal buds that are suppressing the interior growth. This redirect of energy stimulates the lateral buds deep inside the shrub, filling in the “hollow” center with fresh, vibrant foliage. This compact habit not only looks better in a manicured landscape but also provides a much higher density of flower clusters, creating a solid carpet of color rather than a sparse, patchy bloom.